By Alan Mattli

Outside of the world of cinema, the past twelve months have been eventful, to say the least. So compiling a list of my favourite Swiss cinema releases of 2016 felt ever so slightly more significant and tied to real-life goings-on than it did in the past. But maybe that’s just another way of trying to put my opinions into a somewhat more “meaningful” context than would otherwise be the case. Ultimately, everybody can judge for themselves, which is why I will stop hedging now and, after pointing out that Oscar hopefuls like La La Land, Manchester by the Sea, Moonlight, and Jackie (which already makes a strong case for being my Film of the Year 2017) are not in the running here because of their January and February Swiss release dates, get started.

HONOURABLE MENTIONS

In terms of films, this has been a bit of a strange year. Even though I found myself with a pretty fixed shortlist of 13 movies competing for a spot in the top ten, I couldn’t bring myself to allow fewer than 18 movies into my larger best-of selection. So in the following, you will read some of my thoughts on the eight honourable mentions (highlighted in bold) that made the cut this year.

As will probably become obvious when the Academy Award nominations roll around in three weeks or so, 2016 has been an above-average year for animation. Pixar provided us with an almost-better-than-the-original follow-up to 2003’s Finding Nemo, Switzerland rose to international prominence with the both delightful and melancholic stop-motion marvel Ma vie de Courgette (which opens in Switzerland in February), Japanese Studio Ghibli co-produced the wondrous quasi-silent La tortue rouge, and anime proved its global resilience in a post-Miyazaki (or not) world with Your Name and Miss Hokusai.

Almost symptomatically, Disney, the icon of animation itself, delivered the goods this year with two truly excellent productions – Byron Howard and Rich Moore’s socially conscious animal fable-cum-neo-noir thriller Zootopia, and Moana, a progressive princess fairy tale based on Pacific mythologies, directed by Ron Clements and John Musker (The Little Mermaid, Aladdin, The Princess and the Frog). In their own way, both address issues that are highly relevant to a world grappling with resurgent authoritarianism: Zootopia addresses sexism, racism, and prejudice whilst simultaneously telling an arresting buddy-cop story with marvellous humour. Moana, meanwhile, furthers the project of Pocahontas, Mulan, and The Princess and the Frog by adding another princess of colour to the Disney canon, all the while dealing with Polynesian, Hawaiian, and other Pacific mythologies in a exquisitely playful, funny, yet respectful manner. Plus, Moana might just be one of the most beautiful CGI movies ever made.

Another group of movies I would like to highlight here – and which will be extended in the actual top ten – is concerned with the challenges brought about by the current economic climate. It includes Andrea Arnold’s immediate, abrasive, lived-in road movie American Honey, Stéphane Brizé’s quiet blue-collar worker story La loi du marché (The Measure of a Man), and Jia Zhangke’s ambitious vision of the emotional cost of Chinese capitalism, the gorgeously titled Mountains May Depart.

Carried by the fantastic performances of Sasha Lane and Shia LaBeouf, American Honey explores current incarnations of the American Dream, where geographic mobility replaces, rather than supports, social mobility, where younger generations are faced with the breakdown of a system established and gutted by their elders, where empathy and neoliberal ruthlessness struggle to coexist. Similarly, Mountains May Depart, its three parts set in 1999, 2014, and 2025, respectively, traces the fates of mother, father, son, and spurned lover against the backdrop of China’s ever-expanding global power. Not quite allegory, not quite melodrama, Jia’s film fascinatingly suggests intricate links, dependencies, and power balances that complicate the image of China as an unstoppable financial and cultural force. On a much smaller scale, La loi du marché, starring the excellent Vincent Lindon, offers an intimate yet borderline Marxist dissection of the dehumanising effects of a market economy, implicitly advocating a world where humanity is pervasive instead of limited to after-work hours.

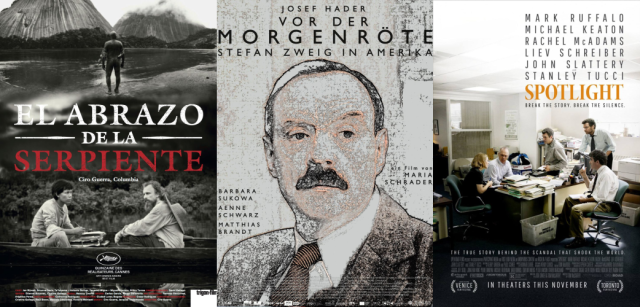

Finally, my honourable mentions include three “historical” films – Ciro Guerra’s Oscar-nominated black-and-white marvel El abrazo de la serpiente (Embrace of the Serpent), which formulates a powerful postcolonial response to European and North American conceptions of paradise and history; Maria Schrader’s sombre portrait of Stefan Zweig’s meanderings through the Americas, Vor der Morgenröte (Stefan Zweig: Farewell to Europe); and 2016’s surprise Academy Award winner for Best Picture, Tom McCarthy’s highly efficient journalism drama Spotlight.

Based on early 20th-century diaries by Western adventurers, Guerra’s Amazonian spin on Heart of Darkness makes for an interesting companion piece to Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, in that it grants ultimate narrative agency to its main indigenous character (played to perfection by Nilbio Torres and Antonio Bolívar) and serves as a stark reminder that, all things considered, the era of the conquistadores is now. Vor der Morgenröte, in parts, takes place in the same general area, chronicling the unfurling dilemma of the pacifist Zweig (a genuinely haunting performance by Austrian humourist Josef Hader) as things increasingly move beyond peaceful resolutions in far-off Nazi Germany. Schrader’s is a timely film about a historical figure championing art, liberalism, and Enlightenment ideals during a period in which that made him seem hopelessly antiquated – a conundrum that eludes easy answers.

By comparison, Spotlight almost seems like standard fare at first glance. But what McCarthy delivers with another finely crafted film, following little-seen gems like The Station Agent and Win Win, is a captivating portrait of Boston’s institutions working together to keep in place the overbearing power of the Catholic Church, told from the perspective of a group of Boston Globe journalists researching the city’s general inaction regarding Catholic priests’ rampant child abuse offences. It is a testament to journalistic integrity and the sacrifices made by individuals to hold those in power accountable to their actions – and it’s rivetingly told as well.

–––

THE TOP TEN

10

Kubo and the Two Strings

Disney has had a phenomenal year with its potent double header (triple, if you count Pixar’s Finding Dory) of Zootopia and Moana, but the laurels for the best animated movie of 2016 go to the astounding stop-motion tour de force Kubo and the Two Strings, courtesy of Laika Entertainment, of Coraline, ParaNorman, and The Boxtrolls fame. Directed by Travis Knight, Kubo is set in ancient Japan and follows a young boy with magical powers (voiced by Art Parkinson), a talking monkey (Charlize Theron), and a cursed samurai who has been turned into a giant beetle (Matthew McConaughey) as they look for ancient artefacts that would allow Kubo to defeat his evil aunts (Rooney Mara) and the ghostly Moon King (Ralph Fiennes). What sounds like a run-of-the-mill hero’s journey is in actuality a surprisingly dark, emotionally resonant and rewarding film about family, friendship, empathy, and grief. Coupled with breathtaking visuals and a strain of sly humour that complements the overarching melancholy, this makes Kubo not just Laika’s most impressive production to date but also one of 2016’s standout movies.

9

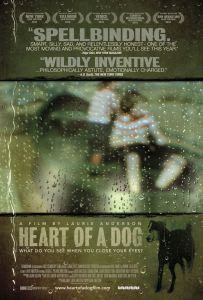

Heart of a Dog

Even though most will know her for her musical output, Laurie Anderson is also an accomplished filmmaker, as illustrated by her latest work; the essayistic cinematic epitaph Heart of a Dog, dedicated to her deceased rat terrier Lolabelle (and formally inscribed to her late husband Lou Reed). The film has been deemed a documentary by the Academy, where it made the final shortlist for the 2016 Oscars, but to hold it to that limiting definition is to constrain its grace and poetry. Taking Lolabelle’s imagined voyage through the bardo – the state between life and death in Tibetan Buddhism – as her starting point, Anderson links animated philosophical and religious musings with home footage of her dog playing the piano, memories of living in New York during 9/11, and the construction of an NSA dataveillance site. Heart of a Dog is not interested in being a linear, thoroughly coherent memorial for a beloved pet. Rather, not unlike Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s dog in the eponymous beat poem, it subtly mimics the sudden changes in mood and interest dogs are wont to express, painting a fascinating and heartfelt portrait of an artist’s inner life in turmoil.

8

Ghostbusters

Let me counter the Internet’s vile misogynistic backlash against Paul Feig’s reboot of the cult Ghostbusters franchise with a backlash of my own: Ghostbusters is one of 2016’s best films. Moreover, it’s also better than the original. Granted, I did not grow up with Ivan Reitman’s entries – which, in my opinion, are perfectly entertaining 1980s horror comedies –, so I might be missing their nostalgic value. I do know, however, that neither of the latest outing’s two predecessors made me laugh as much or be as invested in the action unfolding on-screen. With SNL veterans Kristen Wiig, Melissa McCarthy, Leslie Jones, and Kate McKinnon at the helm – McKinnon’s hilariously unpredictable Dr. Jillian Holtzmann being the year’s standout movie character –, this Ghostbusters excels at quick-witted verbal as well as expertly executed physical comedy. Feig interlaces this winning combination of slapstick and uproarious non-sequiturs (“Our president is a plant!”) with a charmingly schlocky aesthetic that recalls the 3-D movies of the 80s and some genuinely rousing action sequences that make obvious the gross underrepresentation of women in the action genre. It may not be quite Mad Max: Fury Road, but cheering on Wiig, McCarthy, Jones, and McKinnon as they tear the spectres of Puritan pilgrims to shreds gave me one hell of a rush.

7

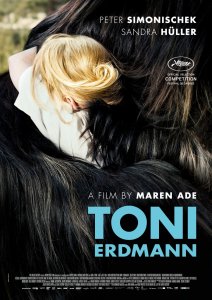

Toni Erdmann

This joke has been done to death, but I will reiterate nonetheless, because the fact it conveys never ceases to amaze me: arguably the best comedy of the year is a three-hour German art house film about Europe’s shifting financial and cultural boundaries. Starring the great Peter Simonischek as a mild-mannered prankster paying his thirty-something daughter Ines (Sandra Hüller) a visit in Bucharest, Toni Erdmann is at once a touching parent-child story, a sly farce with shades of Helge Schneider and Loriot, and a biting satire of modern imperialism. Director Maren Ade, whose last feature, 2009’s Alle anderen, did not resonate with me at all, has crafted a remarkable film that throughout its running time keeps going off in directions you couldn’t possibly predict. While Alle anderen relied too much on cringe humour for my tastes, Toni Erdmann strikes the perfect balance between unpleasant clashes of radically different worldviews – here’s Ines’ dad dressing up as bucktoothed life coach Toni Erdmann, there’s his daughter’s stuffy and clueless work associates – and a subtly absurdist sadness about comically miscalculated priorities in a version of modern adulthood that’s had every ounce of fun sucked out of it. As Ade’s incredibly perceptive vision starts seeping into your mind, you realise that if you can’t laugh about the farcical goings-on on screen, the only option would be to cry. And that would be the real tragedy.

6

The Hateful Eight

As I wrote in my original review, I’ve never been a big fan of Quentin Tarantino. Some of his films I like (Pulp Fiction, Inglourious Basterds), some I’m indifferent to (Reservoir Dogs, Kill Bill, Django Unchained), some I dislike (Death Proof, parts of Kill Bill). With The Hateful Eight, however, I finally found solid common ground. As a big fan of the western genre as a whole, I immediately fell in love with Tarantino’s slow-burning chamber play about a group of despicable ne’er-do-wells seeking shelter from a snow storm in a Wyoming general store, some years after the Civil War. A very game cast featuring Samuel L. Jackson, Kurt Russell, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Walton Goggins, Tim Roth, Demián Bichir, Michael Madsen, and Bruce Dern acts out the grievances of the Reconstruction Era – which are transferable to post-9/11 America, if one is so inclined – in a gorgeously deliberate yet highly entertaining fashion. The Hateful Eight showcases the best of Tarantino; from his knowledge of film history – you won’t find many 21st-century westerns that are as true to form – to his artful dialogues. Combine this with his typically postmodern edge – less forced and more playful than in Django –, the exquisite production values, and Ennio Morricone’s brilliant, horror-imbued score, and you have not just my favourite Tarantino movie but also one of 2016’s best.

5

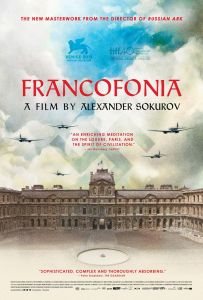

Francofonia

If you’ve seen 2002’s Russian Ark – notable, apart from being shot in a single, uninterrupted 96-minute take, as one of the best films of the 2000s –, you’ll know that no-one takes on historical narratives in quite the same way as Russian director Alexander Sokurov. After dissecting Saint Petersburg’s Hermitage Museum as a place that enshrines, entombs, celebrates, manipulates, displays, and decontextualises the past in the 2002 film, he sets his sights on the Louvre in Francofonia, a thinly veiled spiritual sequel. While Russian Ark staged museums’ inherently fragmentary nature through one-take unity, Francofonia performs fragmentation at nearly every level: it mixes documentary elements with historical reenactments and wholly fictional scenes; it changes the filmic format; it includes fictionalised conversations by Sokurov himself; it makes visible the audio track at times. Focusing mainly, but by no means exclusively, on the Louvre’s fate during the German occupation of Paris, Sokurov mounts a multi-layered examination of the museum’s role in the cultural history of Europe – going as far as gently raising fascinating, intriguing, sometimes also troubling questions about the notion of a pan-European culture. In a film of considerable humour and intimate emotion, one is confronted with sweeping challenges to reflect on one’s continental identity. After all, if one wants to think in European terms, one has to conceive of the Enlightenment and the Holocaust as connected chapters within the same narrative. Francofonia is an awe-inspiring film born out of a disillusioned age, where Brexiteers can rail against the EU whilst invoking “European values” with nationalist pride.

4

Juste la fin du monde

After liking Laurence Anyways, Tom à la ferme, and Mommy to varying degrees, I was instantly mesmerised by the latest project of Xavier Dolan, Canada’s 27-year-old directing boy wonder. Even though Juste la fin du monde (It’s Only the End of the World) scooped up its fair share of scathing reviews after premiering in Cannes last May, I wouldn’t hesitate to call it Dolan’s best so far – keeping in mind that I have yet to see J’ai tué ma mère and Les amours imaginaires and that I owe the wonderful Mommy another viewing. With a high-profile cast (Nathalie Baye, Vincent Cassel, Marion Cotillard, Léa Seydoux, Gaspard Ulliel) at his disposal, Dolan tells the story of a prodigal son, the successful writer Louis (Ulliel), returning home after a twelve-year absence to tell his dysfunctional family about his terminal illness. Shot in often suffocating close-ups, Juste la fin du monde makes for an intense, immediate, heartfelt, beautifully realised family drama open to all kinds of interpretations. Is it a religious allegory, casting Louis’ return as the second coming of Jesus bringing about the titular end of the world? Or does it follow up on Laurence and Tom, in that it explores the consequences of suppressed sexualities? It may sound clichéd, but Dolan’s latest is one of those movies that warrant extensive discussion, where the narrative gaps are there for the viewer to provide their own take on what unfolded on screen. As a consequence, there is little point in me trying to further describe the hidden pleasures of this marvellous drama. It’s still in Swiss cinemas – go see it.

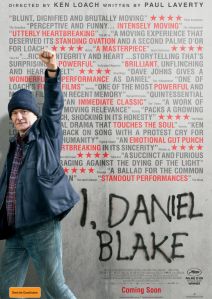

3

I, Daniel Blake

It’s easy to dismiss Ken Loach’s second Palme d’or winner as just another entry into his filmography that chronicles the British working class’ struggle against a hostile neoliberal system. While it certainly is that – in it beats the same left-wing populist heart as in Kes, Looks and Smiles, Riff-Raff, Raining Stones, It’s a Free World…, and The Spirit of ’45 –, the impact it has is intensified both through historical context and Paul Laverty’s perhaps most ruthless script to date. Following a similarly episodic structure as La loi du marché, I, Daniel Blake offers a harrowing look at an out-of-work joiner (played by comedian Dave Johns) who, recovering from a heart attack, is deemed too ill to work by his physician but who doesn’t rank sick enough to qualify for sickness benefits. Loach and Laverty, who base their story on first-hand accounts of unemployed Britons, don’t pull any punches as they send Daniel Blake on his Kafkaesque quest to make a living off rigorously contingent unemployment benefits. Many of the scenes the film matter-of-factly fades in and out of – such as a haunting sequence set in a food bank – paint a grim picture of poverty in the modern UK, offering a powerful counternarrative to those offered by Britain’s pro-Brexit tabloid press, which likes to compare welfare recipients to parasites. 50 years after his debut, Loach’s message remains as potent and as urgent as ever, reminding us of the need to actively care for the socially weak and marginalised, as the system they are stuck in continues to fail them.

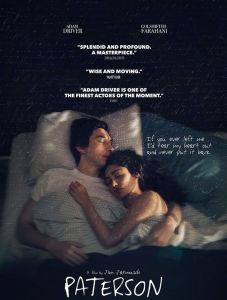

2

Paterson

If I, Daniel Blake offers a sobering look at a world as it exists today, Jim Jarmusch’s lyrical, beautifully simple Paterson is a vision of a world as it could, if not should, be. Set in Paterson, New Jersey, it charts a week in the life of Paterson (Adam Driver), a bus driver who writes poems in his free time. As we’ve come to expect from Jarmusch by now – considering films like Down by Law, Mystery Train, Night on Earth, Dead Man, or The Limits of Control –, there’s not much happening here: Paterson gets up, goes to work, writes a bit, drives around listening in on the conversations of his passengers, returns home to spend time with his wife Laura (Golshifteh Farahani), before he takes his dog for a walk and stops by his favourite bar for a beer. Jarmusch doesn’t seek out conflict; like Paterson’s poet hero, New Jerseyan William Carlos Williams, he’s content to let small, seemingly insignificant events unfold in order to stress and capture their oft-overlooked beauty. An up-and-coming rapper (played by the Wu-Tang Clan’s Method Man) trying out his rhymes in a laundrette, a little girl reading Paterson her poetry, the musings of two teenage anarchists (played by Moonrise Kingdom leads Kara Hayward and Jared Gilman), a street gang interested in dog-breeding – Paterson is an arrestingly peaceful collection of little moments that celebrate the joy of life’s idiosyncrasies. In the shadow of an imminent Trump presidency, Jarmusch reminds us of the happiness and the fulfilment that are to be found in the mundane.

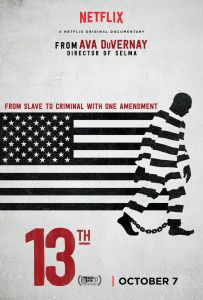

1

13th

I don’t think I ever experienced a more difficult process of finding my Film of the Year. There have been close years in the past – 2013 comes to mind –, but in 2016, it feels like any one of my, say, top seven could have topped the list. The fact that in the end, I chose the Netflix documentary 13th is thus in need of special elaboration. First of all, Selma director Ava DuVernay’s film is a stirring contribution to America’s current debate on race: 13th takes as its starting point the year 1865, the year the Civil War ended after President Abraham Lincoln signed into law the 13th amendment to the United States Constitution, which forbids the enslavement of people. It does, however, contain a loophole: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude” are legal in the US, “except as a punishment for crime”. DuVernay, with the help of a venerable array of mostly Black scholars and activists by the likes of Angela Davis, Senator Cory Booker, and Jelani Cobb, then chronicles the systematic exploitation of that loophole from Reconstruction to the Civil Rights Movement, before tackling the so-called “prison-industrial complex” – the unholy alliance between private industry and the American penal system. 13th carefully traces the development, the cultivation, and the utilisation of the racist “Black thug” stereotype through modern American history, increasingly picking up speed and intensity as it connects Reconstructionist quasi-slavery – the notorious chain gangs – to today’s gross overrepresentation of Black men in America’s prison population, itself far and away the largest in the world. DuVernay and her interviewees – which include a surprisingly perceptive Newt Gingrich – eloquently contextualise the righteous plea of Black Lives Matter, the realities of white privilege in contemporary America, and the importance of forcing a conversation about the prevalence of Black disenfranchisement. What ultimately puts this essential documentary atop my top ten of 2016 is its significance in this cultural, political, and ideological moment: in the year of Trump, the year of white male anger, the year of racism and misogyny being reintroduced into serious circles, the year of “post-truth”, it seems more than fitting to honour a documentary made by a Black woman about the reality of systemic racism. 13th embodies filmmaking at its finest – courageous, vocal, empathetic, and challenging.