By Alan Mattli

Here we go again. Another year has passed, another 52 weeks’ worth of new movies coming out in Switzerland. And it just wouldn’t feel right if I didn’t count down the very best of them. So if you are looking to stay in until New Year’s Eve to digest your numerous Christmas dinners, why not watch some films while you’re at it? As always, some awards season hopefuls – like Room, The Hateful Eight, or The Revenant – only hit Swiss cinemas in the new year, which is why they don’t feature on my 2015 list. But even without them, this year has indeed turned up quite a few memorable films.

HONOURABLE MENTIONS

Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)

While I did not necessarily agree with the Academy’s decision to award this film the Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Screenplay (I was in the Boyhood and The Grand Budapest Hotel camps), there is no denying that Alejandro González Iñárritu’s tongue-in-cheek meta drama about an aging superhero actor (played by the ex-Batman Michael Keaton) trying to revitalise his career on stage ranks as one of the most fascinating films of the last Oscar season. Made to look like it was filmed in a single take, it’s a marvellously acted, fiendishly clever meditation on art, celebrity, and remembering in the age of Facebook and YouTube.

Les combattants

The future of French cinema is in safe hands. Not many countries can boast a similarly impressive array of talented young filmmakers. One such talent broke onto the scene during the 2014 Cannes Film Festival: Thomas Cailley’s debut feature Les combattants (English: Love at First Fight) about two bored twentysomethings (Adèle Haenel and Kévin Azaïs) joining the army, which was given an international release only this year, is at once an arrestingly subversive romantic comedy and a perceptive portrait of youthful ennui in contemporary France.

Ex Machina

Another successful directing debut, the science-fiction drama Ex Machina by British novelist (The Beach) and screenwriter (28 Days Later) Alex Garland is an enthralling chamber play revolving around a genius inventor (Oscar Isaac), his creation – a near-perfect robot (Alicia Vikander) –, and a programmer (Domhnall Gleeson) who has to test just how human said robot acts. Not only does the film fit perfectly into the postmodern canon of works dealing with the fuzzy boundary between humans and machines, but it is also a brilliant showcase of Garland’s abilities as a director and a stylist. Few films of 2015 reach the aesthetic and atmospheric heights of Ex Machina.

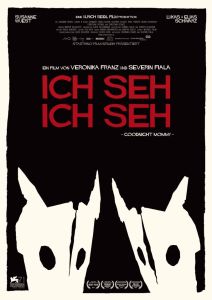

Ich seh ich seh

Distributed internationally with the less sinister, more playfully wicked title Goodnight Mommy, this Austrian art-house horror film by Veronika Franz and Severin Fiala proves that sometimes atmosphere does indeed trump plot. Because even though some of the film’s revelations can be guessed relatively early on, it remains a terrific – and terrifying – mood piece throughout. The story of two twins (Elias and Lukas Schwarz) living in a secluded villa with their mother (Susanne Wuest), recovering from plastic surgery, turns the table on body horror and otherness while successfully drawing on the filmmaking philosophies of Ulrich Seidl and Michael Haneke.

National Gallery

How much time are you willing to spend on watching uncommented footage from London’s National Gallery? In National Gallery, 85-year-old Frederick Wiseman, master of the fly-on-the-wall documentary format, takes his audience on a three-hour tour of the famous museum – lingering in front of paintings, peeking behind the scenes of the massive institution, observing tour guides and other filming crews. It’s an awe-inspiringly simple work of incredible depth, encouraging the viewer to think about art itself and what the very fact of exhibition does to the individual work.

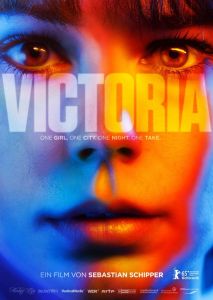

Victoria

Birdman digitally creates the illusion of a one-take film, Victoria goes all the way. Sebastian Schipper and DP Sturla Brandth Grøvlen took on the challenge of making a 140-minute movie in one single take, and the result is a hypnotic crime drama about wayward youth in the streets of early-morning Berlin with shades of Oh Boy, Menschen am Sonntag, Before Sunrise, and Dog Day Afternoon. There may be flaws in the construct, but they are easily overlooked in the face of the sheer accomplishment of pulling off such a stunt.

Whiplash

In spite of surrendering to narrative convenience at the very end, Damien Chazelle’s sophomore feature is one of the most meticulously crafted films to come out of Hollywood in recent memory. Focusing on the struggle of a student drummer (Miles Teller) with his tyrannical jazz school teacher (J. K. Simmons, whose excellent performance won him an Oscar), Chazelle’s psychological drama is as compelling as it is intricately constructed and executed, sporting sharp, precise editing, and a fabulous use of jazz music. Read my full review.

–––

THE TOP TEN

10

Taxi

It’s a small miracle that this film even exists. After being arrested because of his involvement in the protests surrounding the controversial 2009 re-election of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, director Jafar Panahi was handed a 20-year ban on travelling outside of his home country, giving interviews, and, most importantly, making films. He has since contravened this prohibition three times, each time under considerable danger to himself and his family; first in 2011, when he documented the wait for his official sentencing in This Is Not a Film, then in 2013’s Pardé, filmed in his beachfront villa by the Caspian Sea, and now in 2015, when he wrote, directed, shot, and edited Taxi. Much like This Is Not a Film, Taxi engagingly blurs the line between fact and fiction, highlighting the state of limbo Panahi – and countless other, less high-profile Iranian artists – finds himself in. The conversations in his latest coup de main may be staged (and acted out by anonymous non-professionals), but the premise is fraught with a very real danger. Set in a cab driven by Panahi himself, the film’s focus lies on the undercover director chauffeuring people from all kinds of social backgrounds around Tehran – whilst trying not to attract the attention of the authorities. The way his real-life situation bleeds into the fiction of the film – which even in its more serious-looking moments manages to be extremely funny – not only underlines the deplorable conditions critical voices face in Iran, but it also furthers the analytic interest Panahi, ever since This Is Not a Film, has taken in what a cinema of censorship might look like, and whether it can be called a cinema at all. So Taxi is both an incredible act of courage and a highly intelligent, unfalteringly humorous exploration of the possibilities (or lack thereof) of film itself.

9

La isla mínima

It would be easy to dismiss the ten-time winner at the 2015 Goya Awards (the Spanish Oscars) as a straightforward piece of thriller entertainment. Alberto Rodríguez’s La isla minima certainly is that, but that doesn’t tell the whole story. Marshland, as the film is known in the English-speaking world, tells the story of two Madrid detectives (played by Raúl Arévalo and Javier Gutiérrez) who in 1980 are sent deep into the Andalusian backwoods to solve the mystery of two sisters’ sudden disappearance. While it does deliver genre-appropriate suspense and exciting chase scenes, there is also an undercurrent of coming to terms with recent Spanish history at work here. The two protagonists, both anything but flawless in character, are thrown into a rural community where socialist movements clash with rich landowners, whose power is propped up by the still influential remnants of Francisco Franco’s fascist regime. From the muddle of ideologies and interests on display – juxtaposed by some gorgeous map-like shots from a bird’s eye view –, Rodríguez lifts a poignant tale of crime, friendship and forgiveness that never skirts complexity and moral ambiguity in favour of easy resolutions.

8

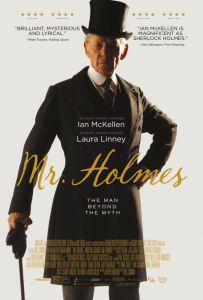

Mr. Holmes

Bill Condon’s screen adaptation of Mitch Cullin’s 2005 novel A Slight Trick of the Mind is one of the best things to come out of the recent renaissance of Sherlockiana. In this version, set in 1947, Sherlock Holmes, who is given a majestic incarnation by the great Ian McKellen, is 93 years old, retired, and spends his days not in 221B Baker Street but in a seaside cottage in Sussex, where he keeps bees and, battling old age, tries to piece together the details of his last case. It’s a beautifully elegiac monument to literature’s most fabled logician that seamlessly fits into the Holmes canon without being too overtly shackled by it. With its stately narrative and marvellous grasp on its main character, Mr. Holmes asks potent questions about the fickle nature of knowledge and memory and cannily hints at the potentially problematic sense of closure Sherlock’s cases usually grant both the figure and the reader. Life, Condon and screenwriter Jeffrey Hatcher argue, transcends cold deduction; their story, ultimately, is one of learning to embrace imperfection and openness. And, helped by McKellen, they tell it in a magnificently human way. Read my full review.

7

Carol

Patricia Highsmith’s groundbreaking queer novel The Price of Salt (1952) – groundbreaking because unlike other LGBT-themed books of its time, it did not saddle its characters with a catastrophic ending – is given stellar screen life in Todd Haynes’ first film since 2007’s I’m Not There. Carried by two outstanding central performances by Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara, it details the love story between a young shopgirl (Mara) and a more mature divorcee (Blanchett) against the backdrop of the coercively harmonious early Eisenhower era. In keeping with the spirit of Highsmith’s source material, Carol does away with the convention of having characters question their sexuality, opting instead to completely normalise – and in doing so, quietly celebrate – the lesbian romance at its centre. This makes for a beautifully poetic film in which, courtesy of writer Phyllis Nagy, each piece of dialogue, every pause, every look, is steeped in subtle yearning and passion – an effect that is strengthened even more by the impeccable production values and Edward Lachman’s brilliant camera work.

6

45 Years

After dazzling international audiences with the LGBT dialogue drama Weekend in 2011, Andrew Haigh’s follow-up feature proved to be equally potent in its careful dissection of a relationship. 45 Years‘ focal point is a pensioner couple (Charlotte Rampling and Tom Courtenay – both brilliant), whose married life is thrown into disarray when he learns that the body of his former girlfriend, who disappeared into a glacial crevasse in the Swiss Alps in the 1960s, has been found. Like Carol, Haigh’s film puts a lot of emphasis on the intricacies of conversations; highlighting hesitant pauses and deferring platitudes as highly significant parts in the puzzle that the potentially disintegrating marriage turns out to be. As far as such dramas go, this is an exceedingly quiet specimen, preferring the lingering look and the air of simmering resentment and disappointment to more grandiose signs of marital strife – all the while purposefully probing the notion of eternal love through the central image of the frozen lover. 45 Years does not further the belief that such love is impossible – if anything, it’s a gentle homage to long-term marriages –, but it does deal with the work that is involved in such an endeavour, leaving the audience with a conflicting yet pitch-perfect open ending, whose gaps each viewer must fill in according to their own disposition. Read my full review.

5

Mad Max: Fury Road

I’ve gone on about my strangely subdued relation to action films for quite some time in my review of this film, so there is no point in going into too much detail what stance I – or rather, my adrenaline – take on being confronted with lots of explosions. And yet, the fourth installment of Australian director George Miller’s post-apocalyptic brainchild, the vehicle-centered Mad Max franchise, which has lain dormant for 30 years, comfortably makes my list of the best films of 2015 – and may rise even higher in my esteem as I rewatch it over the coming years. The reasons for this are manifold. Yes, there is the action – gritty, intense, mind-blowingly fast-paced, no-holds-barred. With the help of Tom “Junkie XL” Holkenborg’s rousing score – Wagnerian opera meets heavy metal – and DP John Seale’s breathtaking imagery – the year’s finest cinematography, without a doubt –, Miller conducts a veritable orchestra of gunfire, car crashes, and explosions that will leave you breathless right until the credits roll. But although the already minimal dialogue may be dwarfed by the sheer scale of on-screen destruction, Mad Max: Fury Road, on whose script Eve Ensler of The Vagina Monologues fame served as a consultant, also offers a hefty, whip-smart rebuttal to the cliché that action cinema should be inherently phallocentric. Indeed, Max (Tom Hardy) is an incapacitated onlooker for much of the film’s first half, yielding centre stage to Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron), who hijacks a tank convoy of a maniacal desert cult leader (Hugh Keays-Byrne) to cart off his wives to safety. Fury Road, with its strong female individuals – Furiosa at the helm – and its almost comically wasteful brandishing of phallic guns, takes a roaring feminist stand against cinema’s perhaps most sexist genre, shouting, “Women are not things!”. Right on.

4

Inside Out

Once a shoo-in for any “Films of the Year” list, Pixar has, ever since 2010’s Toy Story 3, become the victim of people’s outsized expectations. Brave and Monsters University, for instance, while very good, just did not seem to be quite on the same level as the reliably outstanding fare the studio produced during the 2000s; from Monsters, Inc. and The Incredibles to Ratatouille and WALL-E. But with Inside Out, the animation giant produced a stunning reminder of why it enjoys such an excellent reputation. Set mainly in the mind of an eleven-year-old girl (voiced by Kaitlyn Dias), the film details the life of her primary emotions; Joy (Amy Poehler – brilliant), Anger (Lewis Black – brilliantly funny), Fear (Bill Hader – ditto), Sadness (Phyllis Smith – wonderful), and Disgust (Mindy Kaling – also wonderful). In true Pixar fashion, Inside Out perfectly balances an infectious sense of fun with a serious, touchingly wistful core. As the human protagonist’s family moves to San Francisco, where life proves to be far from ideal, Joy and Sadness get lost in the furthest reaches of the human mind, leading not only to an arresting quest through numerous thought processes but also to the very mature realisation that sometimes the past has to be left behind in order to progress as a person. Where other films aimed at children stick to the coddling myth that everything is retrievable and salvageable, Inside Out beautifully embraces the fact that life is, for better or worse, more complex than that. Read my full review.

3

A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence

Certainly the strangest film of the year, Swedish director Roy Andersson’s conclusion to his self-described “Living trilogy” (the other entries being 2000’s Songs from the Second Floor and 2007’s You, the Living) is a unique, endlessly fascinating piece. A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence – inclusion into any top ten could be justified by the title alone – consists of 39 “sketches”, most of them narratively isolated, almost all of them shot in a single static take, featuring sadsack characters in eerily pale make-up that drift through a dismal, grey-brown version of Gothenburg. There are two hapless joke article salesmen who constantly fail to pique potential buyers’ interest; there’s Swedish King Carl XII and his troops, on their way to the Russian campaign of 1708, making a pit stop in an outskirt bar; there are bizarrely banal deaths, irksome misunderstandings, and even an impromptu musical number. In short, this film is radically different from anything you are used to seeing in cinemas, even if you consider yourself well versed outside of Hollywood productions. It is exactly films like this one I like to point to when the argument arises that creativity has deserted cinema for television. Like the best artists, Andersson, a veteran director of TV ads, illustrates the lasting power of the cinematic format, offering up a distinctive, by turns funny and disturbing vision of humanity.

2

The Look of Silence

In the second half of his documentary diptych, part one being 2012’s The Act of Killing, Joshua Oppenheimer returns to Indonesia to portray a society that is built on the celebration of barbarous mass killings of alleged communists that took place between 1965 and 1966. 50 years on, the purges are either glorified or glossed over, the perpetrators venerated as heroes by the public as they continue to occupy high ranks in the country’s military and politics – while the surviving relatives of the victims are systematically excluded from attaining positions of power and are muscled into a culture of forgetting. The Act of Killing dealt with this injustice from the perspective of actual killers; The Look of Silence takes up the position of the victim – just one of the reasons why this second film resonates even more strongly. Here Oppenheimer focuses on Adi, the brother of a man killed in 1965, who visits the people involved in his brother’s violent death under the pretence of giving them a free eye exam, only to calmly confront them about their crimes. It’s a stark illustration of the atrocities human beings are capable of perpetrating and rationalising – as well as a subtle monument to humanism and pacifism, embodied by Adi, who does not seek vengeance but understanding and the ability to forgive. Read my full review.

1

It Follows

2015 was a year of many distinguished films, to be sure, but one that, at least for me, lacked an outright frontrunner. On another day, my top ten might have a different order to it – I might rank 45 Years‘ gentle seriousness above the multi-layered entertainment value of Mad Max and Inside Out; I might give Fury Road‘s feminist streak more weight to place it above the brilliance of Pixar; honourable mentions like Victoria or National Gallery might make the final cut. But as it stands, this is my top ten, filled with, to my mind, more than worthy representatives of 2015 cinema’s finest. To top it off, I have chosen the film which has undoubtedly made the biggest impact on me. If you leave the cinema wanting to write an essay about the movie you just saw, then you’ve witnessed something special indeed. It Follows, a relatively small-budget horror film by David Robert Mitchell, has had that effect (I think you can tell by my lengthy review). Its premise is simple yet nightmarish: after having sex with her boyfriend (Jake Weary), Detroit college student Jay (Maika Monroe) learns that she has contracted a curse from her partner. A mysterious, shapeshifting entity now follows her at a walking pace, bent on killing her. To pass on the ghostly stalker, she has to sleep with someone else. For brevity’s sake, I am not going to try to venture down all the analytical rabbit holes Mitchell’s film opens up, but I will touch on a few of them. It Follows works as a fascinating take on sexuality and society’s treatment of it, as the entity, an STD in all but name, can be read as a metaphor for diseases like AIDS, and the societal shunning of “deviant” sexuality that goes with it. Fear itself is another dominant theme: the brilliant set decoration, for example, which mixes modern and obsolete technologies, can easily be understood as a chronologically anonymised backdrop to an America where paranoia – from Communists to terrorists – is one of the most pervasive motives. And that fear does not look like it will stop anytime soon, as the exclusively young characters seem to be the only ones affected by the dread emanating from the following entity. “It”, then, becomes a symbol of a future without prospects. But Mitchell never forces the point, choosing instead to focus, on the surface at least, on making an effective entry into the American horror canon in the vein of John Carpenter. It Follows recognises the rules of the genre game, and uses them – in conjunction with Richard “Disasterpeace” Vreeland’s amazing, distorted minimalist 8-bit score and Mike Giouliakis’ otherworldly cinematography – to maximal effect. Form and content create a brilliant whole that asks questions which prove to be as haunting as the scares that are provoked. For being one of the most daring, most complex movies to come out of the US in recent years, It Follows deserves to be named the best film of 2015.

Pingback: From Our Members’ Desks (Jan. 5, 2016) – Online Film Critics Society