By Alan Mattli

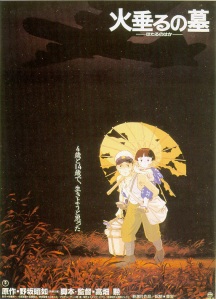

War, particularly the emotional side of it, has always been one of cinema’s most prevalent subjects. Both soldiers’ and civilians’ hopelessness and psychological traumata, as well as images of seemingly senseless violence and destruction have become common tropes of the genre, and movies like Paths of Glory, Schindler’s List, All Quiet on the the Western Front or Saving Private Ryan classics. However, one of the if not the best war films of all time is a singularly unlikely one. Not only was it made by one of World War II’s losing parties, it is also not entirely unsuited for children and, above all, it’s animated. Isao Takahata’s 1988 tragedy Grave of the Fireflies (original: “Hotaru no haka”), which was produced by Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli (Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, Princess Mononoke), is a masterpiece of subtle storytelling, characterisation, and the depiction of the horrors of war, and it is, quite possibly, the saddest animated film ever made.

War, particularly the emotional side of it, has always been one of cinema’s most prevalent subjects. Both soldiers’ and civilians’ hopelessness and psychological traumata, as well as images of seemingly senseless violence and destruction have become common tropes of the genre, and movies like Paths of Glory, Schindler’s List, All Quiet on the the Western Front or Saving Private Ryan classics. However, one of the if not the best war films of all time is a singularly unlikely one. Not only was it made by one of World War II’s losing parties, it is also not entirely unsuited for children and, above all, it’s animated. Isao Takahata’s 1988 tragedy Grave of the Fireflies (original: “Hotaru no haka”), which was produced by Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli (Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, Princess Mononoke), is a masterpiece of subtle storytelling, characterisation, and the depiction of the horrors of war, and it is, quite possibly, the saddest animated film ever made.

The year is 1945, the place is Kobe in southern Japan. During an American air raid the mother of 14-year-old Seita (voice of Tsutomu Tatsumi) and 4-year-old Setsuko (Ayano Shirashi) is fatally hurt, so the two siblings have to find a new place to live. Eventually, they are taken in by a distant aunt, largely because of their stock of alloted food they received due to their father being a high-ranking navy official. As soon as those goods are used up, the aunt turns hostile, forcing Seita and Setsuko to move out. They find an abandoned bomb shelter in which they intend to start a new life as self-supporters.

Considering Japan’s sensitivity concerning their role in the Second World War, Grave of the Fireflies is a rather courageous piece of cinema. Takahata, adapting Akiyuki Nosaka’s 1967 novel, does not gloss over the infamous Japanese wartime fanaticism. But this is not the film’s main focus. Its centre is Seita and Setsuko, their complex relationship and the question of how war affects uninvolved children and adolescents. They give the millions of people who are involuntarily thrown into the clashing of two parties’ ideologies a face, thus hinting at the cardinal absurdity of war. Visually, this is presented in perfectly animated, gorgeously atmospheric images, which recall the technique of Yasujirō Ozu (Tokyo Story), one of the masters of classic Japanese cinema. The imagery is dominated by stark depictions of city districts in ruins or in flames contrasted with the fundamental beauty and tranquility of nature. To a lesser degree, Grave of the Fireflies is also interested in how the general populace’s moral values shift when it adheres to the highly doubtful, and maybe even false, concept of patriotism.

Considering Japan’s sensitivity concerning their role in the Second World War, Grave of the Fireflies is a rather courageous piece of cinema. Takahata, adapting Akiyuki Nosaka’s 1967 novel, does not gloss over the infamous Japanese wartime fanaticism. But this is not the film’s main focus. Its centre is Seita and Setsuko, their complex relationship and the question of how war affects uninvolved children and adolescents. They give the millions of people who are involuntarily thrown into the clashing of two parties’ ideologies a face, thus hinting at the cardinal absurdity of war. Visually, this is presented in perfectly animated, gorgeously atmospheric images, which recall the technique of Yasujirō Ozu (Tokyo Story), one of the masters of classic Japanese cinema. The imagery is dominated by stark depictions of city districts in ruins or in flames contrasted with the fundamental beauty and tranquility of nature. To a lesser degree, Grave of the Fireflies is also interested in how the general populace’s moral values shift when it adheres to the highly doubtful, and maybe even false, concept of patriotism.

But this is by no means heavy-handed, hammered-in subtext. True, it is easy to spot, but it is also completely unintrusive and it doesn’t obscure the heart-wrenching human drama in the least. The two main characters are neither a nuisance nor a mouthpiece for someone much older than them – alwyays a pitfall in this kind of movie – and their experiences, good and bad, are as arresting as they are realistic, even when they are as mundane as Seita taking his sister to the sea, or Setsuko burying the dead fireflies that brought her so much joy as night lights – one of the film’s most achingly beautiful scenes. Throughout Grave of the Fireflies you get to see a lot of the siblings’ inner life and their evolving relationship, which creates a real emotional tie between them and the viewer, so that you genuinely feel for and with them. Much like in the not quite as enthralling but similarly intense adaptation of Raymond Briggs’ graphic novel When the Wind Blows, you won’t be able to turn your eyes away from the film, despite the very graphic portrayal of the heroes’ failing health and their nudging ever closer to their doom. But even if it does make you teary-eyed – despite its quasi-happy ending – which is extremely likely, Takahata’s film is one whose greatness exceeds its depressing potential. It’s the love and compassion we feel between Seita and Setsuko, between brother and sister, that pulls us through.

But this is by no means heavy-handed, hammered-in subtext. True, it is easy to spot, but it is also completely unintrusive and it doesn’t obscure the heart-wrenching human drama in the least. The two main characters are neither a nuisance nor a mouthpiece for someone much older than them – alwyays a pitfall in this kind of movie – and their experiences, good and bad, are as arresting as they are realistic, even when they are as mundane as Seita taking his sister to the sea, or Setsuko burying the dead fireflies that brought her so much joy as night lights – one of the film’s most achingly beautiful scenes. Throughout Grave of the Fireflies you get to see a lot of the siblings’ inner life and their evolving relationship, which creates a real emotional tie between them and the viewer, so that you genuinely feel for and with them. Much like in the not quite as enthralling but similarly intense adaptation of Raymond Briggs’ graphic novel When the Wind Blows, you won’t be able to turn your eyes away from the film, despite the very graphic portrayal of the heroes’ failing health and their nudging ever closer to their doom. But even if it does make you teary-eyed – despite its quasi-happy ending – which is extremely likely, Takahata’s film is one whose greatness exceeds its depressing potential. It’s the love and compassion we feel between Seita and Setsuko, between brother and sister, that pulls us through.

As far as animated films go, there is almost no surpassing Grave of the Fireflies – save for a few selected Pixar gems. Apart from taking a powerful stand against war and poignantly commemorating Japan’s civilian casualties in World War II, it tells a compelling, resonating and deeply haunting (anti-)war story that’s impossible to shake off. If you needed conviction that humanistic war films are the best ones out there, you need to look no further than Grave of the Fireflies – a cinematic masterpiece in its own right.

★★★★★★

I loved Spirited Away and Howl’s Moving Castle, so will definitely have to give this one a watch now…. Thanks for the great review!

Wow! Great rewiev about a truly great film.

Thank you both for the compliments. 🙂

@Ciara

Have you seen “Kiki’s Delivery Service” and “Castle in the Sky”? They’re my Miyazaki favourites.

No, neither — more to put on the list! 😀

Great review! I saw the anime only once and can’t find courage to watch it again, so sad it is (and wonderfully done).